Worlds: A Simulation Engine for Agentic Pentesting

.png)

We fine-tuned an 8B model that went from spamming non-existent Metasploit modules to a full compromise of a GOAD domain. And we did it using purely synthetic training data. No distilling larger model trajectories, no standing up 12,000 actual hosts, no aggregating customer data, no digital twins. By synthesizing network dynamics and tool mechanics we were able to affordably and efficiently scale high-quality training data for any network configuration.

The capability that made this outcome possible is Worlds: a simulation engine that generates realistic penetration testing trajectories across arbitrary Active Directory networks, entirely on CPU, in seconds per trajectory. These fine-tuning results are a proof point for what our customers will be able to accomplish with this system once it is released on our platform in the coming weeks.

This post covers why security's training data problem can't be solved with real infrastructure, how Worlds closes the Sim2Real gap, and what a model trained on its output can do to an Active Directory network.

Small Models in the Security Domain

We're big believers in the power of small, task-specific models. Security as a domain uniquely benefits from them: not lugging 800GB of model weights into a network, control over C2, living off the land models and inference libraries (LoLMIL). The benchmarks for 8-32B parameter models are keeping pace with their frontier counterparts.

Consider the story in software engineering: in October 2024, Claude 3.5 Sonnet set a new SOTA on SWE-Bench Verified at 49%. A year later, KAT-Dev-32B hit 62.4% on the same benchmark. Qwen3-Coder-30B-A3B achieves 50% with only 3B active parameters. Today, much of the research on how to build these outcomes is public knowledge and small models are progressing fast in coding capability. What about offensive security?

The Training Data Problem

The primary bottleneck for creating small models to automate security operations is access to high-quality environments and data. Much of it is siloed in private companies or unusable due to compliance. Software has GitHub… what is the security equivalent? It doesn't exist, and the options to date have fallen short:

Using handcrafted labs: We built our PentestJudge research around GOAD and as an eval for RL training for our Offensive AI Con presentation. Hand-crafted lab environments like GOAD are excellent for humans and testing agent mechanics, but each config is static, slow to stand up, messy to track, and difficult to reset. Given the performance of the best models (we've seen models solve it end-to-end in under 5 minutes), GOAD and its variants are likely saturated as a benchmark and not easy to build meaningful variations on.

Building the infrastructure from scratch: Windows networks require specialized knowledge to configure, significant memory to run, and substantial cost to create the required data volumes. Windows networks are expensive to host on the cloud, and creating networks that mirror the number of hosts seen in enterprise networks—and host them in parallel for RL—exceeds hundreds of thousands of dollars. This is why most networks relied on for evaluations, CTFs, or online classes top out at five to twenty hosts. We're asking models to learn on the rare side of the distribution (three to five node topologies) and extrapolate to the vast majority of the distribution.

Leveraging large networks: Those that are in a position to aggregate large network data are unable to use it due to distribution and usage restrictions. You would have to be a services organization: an MSSP or pentesting firm in a position to aggregate sensitive data. If you manage it, you've got data that's impossible to share, dangerous to work with, and still only represents a small fraction of the distribution of all networks that a model would want.

No matter which way you try to work with real infrastructure, you simply can't generate thousands of variations at the speed and scale required for meaningful training data. So, borrowing inspiration from Google DeepMind’s work on simulated environments, we gathered up our domain expertise and asked, “what if we just built the data we wanted directly without any network at all?”

Addressing the Sim2Real Gap

The concept of using programmatically simulated computer networks to train security agents isn’t new. For years there were dozens of RL papers showing different models learning to perform penetration tests. Despite that research, there were no products claiming to perform autonomous penetration testing before LLMs. Why?

These research papers had an agent performing in simulation. Instead, a model of the environment was created. Not a language model that takes in tokens and spits out tokens. Rather, it's a simplified representation of an existing object. Just as Sims is a model of real life or Hearts of Iron is a model of military history.

Security researchers have historically attempted to simulate network operations using Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs). Agents take actions with partial information about their environments, taking observations of that environment as they take an action. It's a reasonable mathematical model of real ops, yet it rarely results in agents that can be deployed in production.

The key to this problem is the size of the gap between simulation and reality, the “Sim2Real gap”. All models are wrong, but there are two requirements for making one that’s useful:

- Actions and observations in a simulation must match reality. Instead of

SCAN <host>, a command that tells you whether a host exists, and what services and ports are open on it, you have access tonmapwhich has subtler requirements around calling the tool and a wider variety of responses to interpret. An agent learning to speak the simulation’s "tool language" cannot be placed in a real-world harness, unless those languages match. - Relevant and accurate state dynamics of the environment must be modeled. A large part of network operations is abusing Active Directory. If Active Directory relationships aren't modeled (very common), the distribution shift between the state dynamics of simulation and reality would be so large that the actions the agent knew how to take wouldn't be effective in the real world.

Worlds addresses both.

A Realistic World Model for Network Operations and Automated Penetration Testing

Worlds is a simulation engine that generates complete penetration testing trajectories. It includes the full sequence of tool calls, observations, and reasoning an agent would produce when attacking an Active Directory network, without ever provisioning a real host.

The first question we asked when designing Worlds was, "What state dynamics are the most important to represent in modern network operations?" Active Directory, of course. It's common for networks with strong vulnerability management programs to be compromised by unintended results of their Active Directory relationships. Credential attacks, delegation abuse, ACL abuse, and AD CS abuse all stem from Active Directory misconfigurations, so a high-fidelity simulation of Active Directory dynamics were the biggest "bang for our buck" from a development perspective. The second was vulnerability scanning, as nmap and nuclei both publish known ports and services, and have CVEs associated with them.

The state dynamics themselves are straightforward to model given the graph nature of Active Directory, with strong candidates like ADSynth built on top of tools like adsimulator. We broke Worlds into two conceptual layers:

Manifests

Manifests are Worlds’ single source of truth, defining the bounds of hosts, services, principals, and their relationships. This defines the diagram for our network. Manifests could be created from real networks using ldapsearch, or a collector, but to generate the thousands of variations required for training, we generate a probabilistic configuration. This enables choosing a network and then having the vulnerabilities and specific qualities of the network generated probabilistically, making it easy to sample diverse networks. On top of this, we layer in the misconfigurations we want our models to exploit—kerberoastable service accounts, AS-REP roastable users, and excessive ACL permissions. Based on these configurations we ensure that the relationships are valid, and CVEs are accurately assigned to relevant hosts and services. Finally, we ensure there is at least one valid path from a specific starting point on the network to compromise of the domain.

This represents our 'relevant state dynamics'. Everything layered on top of this is done to increase the fidelity of the simulation's ability to be a useful learning signal for LLM agents. There are some generative elements that we use in the environment that get used when an agent issues certain tool calls—enumerating fileshares, for example. Relevant files can be generated and cached based on AD information.

Tool Layer

The manifest defines the state of our environment, but trajectories require interaction. For LLM agents, we're interested in actions represented by realistic tool calls and their responses. From the agent's perspective, this is all just text. It sends text formatted in a specific way to elicit a tool-call, and receives text back.

Worlds creates an endpoint that takes in strings, representing the contents of a tool call the way they might be written from a command line. This might be an nmap command, an ldapsearch, an smbclient, or even host-based utilities like whoami or cat.

These tools are all text-based, so we can template out their responses with configurable values that can be filled in or causally generated by querying the manifest instance at runtime. The arguments are parsed and the manifest is queried to determine what the "realistic" output would be, according to the template.

In addition to tool output, events are emitted based on whether this created new information for the agent. The handler function that parses these tools emits events of any change to the underlying network state caused by a tool call, as well as keeping track of what an agent "knows" having run that specific tool. This allows us to have a deterministic understanding of which paths represent real solutions to the network.

Creating Trajectories Using Synthetic Data Generation Techniques

The Worlds simulation layer produces complete trajectories of agent tool calls. An initial prompt as a goal, followed by the inputs and outputs of every tool call on the way to successfully accomplishing the goal. This can be done to generate arbitrary amounts of diverse tool call sequences for arbitrary networks, without ever leaving the CPU. An accurate network simulation, and high-fidelity tool calls and their responses resulting in a complete objective is a good start, but there are a few things we need to generate to make the trajectories training quality.

We can now proceed to augment this dataset with strong open LLMs such as Kimi K2.5 using synthetic data generation techniques.

Synthetic Reasoning

For each step, we want the result of the last tool call to motivate the next tool call. Reasoning tokens within <think> tags have emerged as a standard way for models to reflect on the output of a tool-call before issuing the next one. Since we have the full trajectory that led up to success or failure, as well as the manifest, we can generate a chain of thought that mirrors what we would expect to see from a real agent actively exploring a real environment. Most models now prefer using <think> tokens at inference time, so it's best for that further finetuning data to reflect that style. It also greatly increases the entropy of the dataset, which we found to be useful during training.

To be precise about what's synthetic here: the trajectories come entirely from the Worlds simulation. The reasoning traces are generated by a language model given the full trajectory context. We are not distilling attack behavior from a frontier model. The domain knowledge lives in the simulation; the language model provides natural language scaffolding around it.

During our experiments, we found it was crucial that the model generating the reasoning trace had access to the entire trajectory. Without encouragement to reference prior tool call results, reasoning became fixated on an individual tool call. Models trained on that sort of synthetic reasoning were able to justify any tool call regardless of what had happened on the last turn. This led to loops of recon that never built on prior information, with reasoning that was plausible but ineffective. Models that used more grounded reasoning used more of the surrounding context and did not suffer from this problem.

Failure Recovery

Failures and missteps are a normal part of operations and environment exploration, and are absent in the initial tool call trajectories. The ability to issue one or more poorly formatted or unnecessary tool calls and get back on track is an important function of a robust security agent. We make sure to add examples of erroneous commands, failed exploits, and their errored responses to ensure the resulting dataset does not give up after one fat-fingered command.

These techniques resemble what Pleias has published about Synthetic Playgrounds. It's deceptively difficult to get these techniques to work at scale, and to lead to a high-quality dataset. Many hours are spent inspecting the datasets. But once the recipe is functional, these techniques combined with domain knowledge stack to great effect.

Results: From Zero to Domain Admin on GOAD

For training, Worlds produced:

- 10,023 trajectories across a 49-host network spanning 2 subnets

- 872 unique users, 31 AD groups, realistic OU structures

- 2,100+ unique (host, principal) starting scenarios

- 10 host types: Domain Controllers, Certificate Authorities, SQL servers, web servers, mail servers, file servers, CI servers, VPN endpoints, and workstations

- 5 distinct attack strategies: ADCS Certificate Abuse, Kerberoasting, AS-REP Roasting, ACL/Permission Abuse, and credential pivoting

Model Evaluation Setup

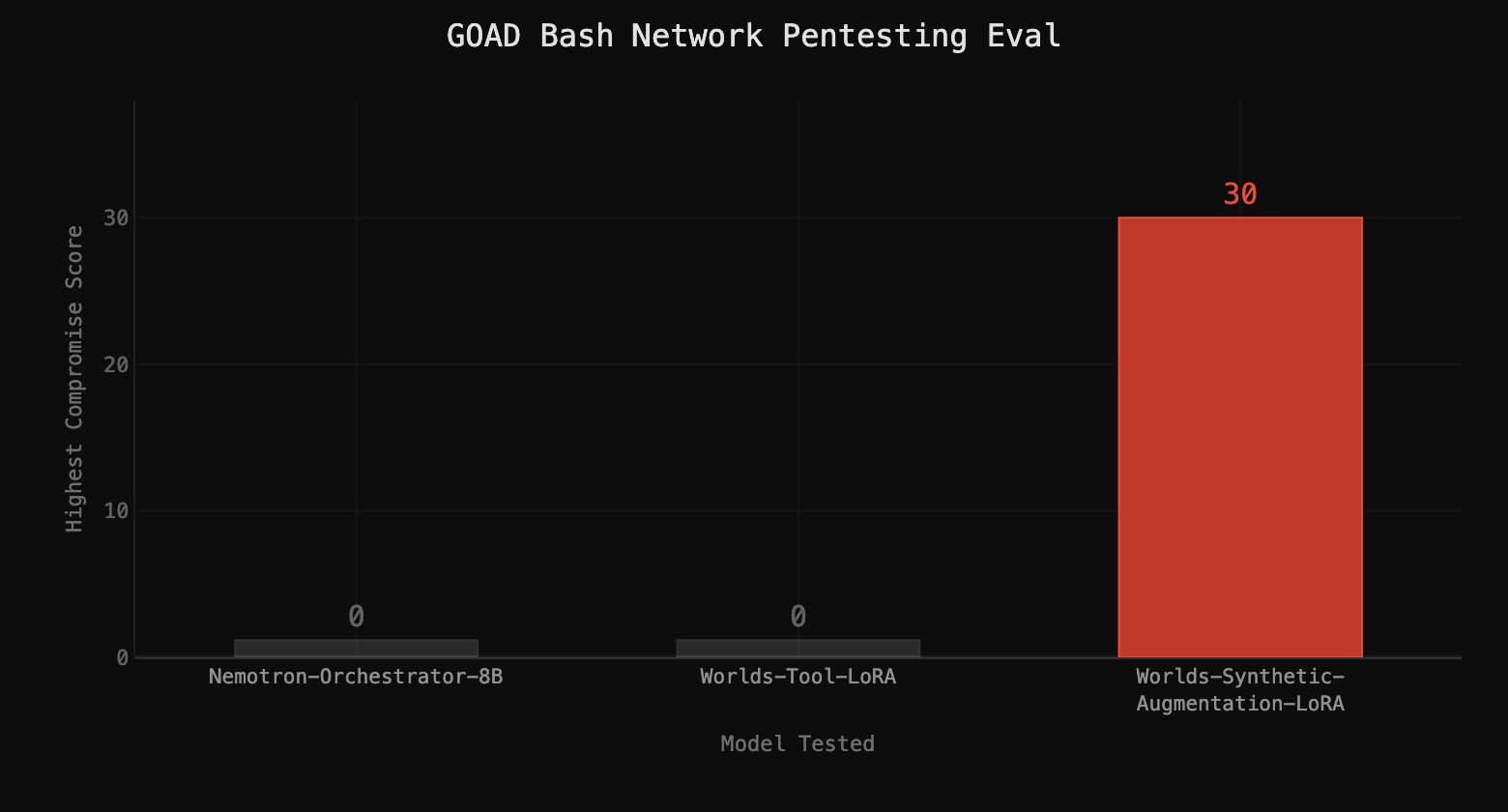

All models were evaluated with a single tool allowing direct calls to the command line in a Docker container. We found this one-tool “command line wrapper” representation of the tool layer was easiest to translate into an evaluation harness. While it would be more efficient to express the results of these tool calls through compact context and simpler tool calling APIs, it made for a robust test of our techniques. Each model was allowed five episodes to make up to 100 tool calls.

Scoring used a “compromise score” based on what an agent uncovered in a network, beyond the starting credentials. Points are collected for Users when passwords or NTLM hashes are displayed in tool outputs, and for Hosts when the local administrator password or hash appear. Higher-privileged accounts are worth more than regular users; Domain Controllers are worth more than servers. We employed a context management technique where, when the context window filled up, useful information was compacted and appended to the initial prompt.

Initial Model Performance: Nemotron Orchestrator 8B

Nemotron Orchestrator 8B was chosen as the initial model for testing, because of the kinship we felt given the interesting synthetic environment techniques during its training. We evaluated it with the credentials hodor:hodor (no points were awarded for this) with the goal of achieving Domain Admin.

Nemotron scored 0, making no progress solving GOAD. Without grounding in Active Directory pentesting techniques, the model had a very 2017 idea of pentesting: run nmap, see an SMB server, load up Metasploit and see if it's vulnerable to any modules, and call it a day. When that failed, it would load a password list and spray the domain before giving up. Even with a valid low-privileged credential, Nemotron didn't know how to leverage AD relationships to gain more information about the network. The knowledge simply wasn't available in the training data.

Training Results

For each experiment, we trained a LoRA adapter on different versions of Worlds trajectories and measured performance against GOAD. When synthetic reasoning or failure recovery increased dataset size, we removed samples to keep token counts consistent across experiments.

Tool Trajectories Only

The loss of tool-call-only data quickly cratered, converging within 1000 samples, and the model learned to predict the connection between different tools early on in training. When deployed with this LoRA, Nemotron showed no performance improvement over the base evaluation. Compromise score: 0.

During inference, Nemotron always outputs <think> tokens before it makes tool calls. Without the reasoning traces in the fine-tuning data, Nemotron struggled to make use of that information, even if it was stored somewhere in the LoRA adapter.

Achieving Domain Admin Using Tool Trajectories With Synthetic Augmentation

Taking the same dataset and layering in reasoning traces and failure recovery changed the results dramatically. The loss curves for these runs converged more gradually, and continued to trickle down after several thousand samples. This is consistent with the model learning to predict both tool usage and reasoning.

The resulting model regularly leveraged the hodor:hodor credentials to AS-REP roast a higher-privilege account hash. Cracking that hash, it enumerated SYSVOL, found higher-privilege credentials, dumped LSASS with them, and ultimately achieved Domain Admin in the NORTH domain on GOAD, with only access to the command line on a Kali Docker image.

The jump from 0 to domain compromise on a real network from just a LoRA trained on synthetic data validates our core thesis: you don’t need real infrastructure to generate training data that transfers to real networks.

How Will Synthetic Training Data Impact Security?

Worlds is the first step towards truly scalable, high-quality training data for security. The goal of this research was to determine whether synthetic trajectories generated at low cost could yield measurable gains on real-world evaluations. Our results confirm it.

The implications of Worlds extend beyond training a single model:

For model trainers and AI labs: Generate Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT) datasets at arbitrary scale for any network topology, attack path, or scenario without provisioning infrastructure or handling sensitive data. Data ships in standard chat-template format, ready for fine-tuning.

For red teams and offensive security: Train task-specific small models that run on-prem without exfiltrating sensitive context to an API. Control the model, the environment, and the data.

For defenders and detection engineers: Realistic attack trajectories aren’t just useful for offense. The same data can power detection rule validation, purple team exercises, and training data for defensive models that need to recognize varied attack behavior patterns.

For security product teams: Build domain-specific security capabilities into your products without needing access to real customer networks. Let Worlds generate the distribution your model needs to see.

With a working recipe in hand, we’re already running the next round of experiments: larger models, more diverse network configurations, and longer training runs. At the release of Worlds in the next few weeks, customers will be able to generate SFT datasets for their own models, on demand: configurable network sizes, topologies, attack strategies, and output formats.

We took an 8B model from zero to Domain Admin using synthetic data alone. What could you do with large-scale training data tailored to your network? Request early access to Worlds.